Allen Smelting Mill & Flue System

Allendale, Northumberland

Last Updated:

6 Dec 2024

Allendale, Northumberland

54.903626, -2.263950

Site Type:

Smelting Mill, Flue System

Origin:

Status:

Partly Preserved

Designer (if known):

Designated Scheduled Monument

In the rolling hills of Allendale you'll find its core industry - the industry that propped up the whole area. Lead. The site outlined below was the principal works in the whole region which brought prosperity to the hills.

The Allen Mill builds upon a lead working site which as stood here since the late 17th century. At this time, the Bacon family will have smelted lead to be used for houses, ammunition and any sort of lining really. This continues through to the 18th century when it was to Sir William Blackett, who leased it out to local mineowners to smelt their own ore. Along with coal this was the industry which expanded the family fortunes, with their influence growing to such an extent their name is still known across the NE. This was even despite great fluctuations in the lead industry in the early 18th century.

It formerly came under the ownership of the Beamonts, Wentworths, Fenwicks and Blacketts in 1786 - all famous North East names. It was them who rebuilt the complex we see below in the 1830s to include 5 roasting furnaces, 8 ore hearths, a refining furnace, 2 reducing furnaces, 2 calcining furnaces, 2 reverbatory furnaces and a slag hearth. Don't ask me what half of those mean, but the key point is it was the key player in the prosperity of this whole area and production vastly expanded in the 19th c.

In fact, if you take a closer look on my first aerial shot you can see extensive remains of the 1830s works. These are reputed to be "bouse teams", which as far as I am aware are big storage hoppers where material was kept before sorting. There is also a condensing champer and a flue opening which is still extant.

In the late 1860s it was connected to rail, and effectively kept the Hexham and Allendale Railway going until it met its own demise. Slumps in lead prices appear to have been constantly fluctuating, and put the whole railway and the works in constant instability.

By the end of the 1890s, the works was no longer viable. In 1852 their world famous mines had an output of over 10,000 tons, more than the whole of the north at the turn of the 20th century. Waggons, stores, tools, stock and machinery were all part of a firesale in 1899 to get rid of all the assets which must have left the families in real embarrassment.

Nowadays this site is an office park.

FLUE SYSTEM

Of course, any dealings with lead are incredibly toxic. The firm took great lengths to transport the noxious fumes to high positions to release the fumes away from lower ground. The fells around here made for ideal sites to exhaust it, but how did it get there?

Well, they constructed giant flue systems from the 1830s to the 1850s, which were basically giant pipes built using cut and cover. There's evidence of these pipes all across the area that look like giant worms have excavated under the surface. Here's two examples at Thornley Gate and Langley.

The flues were hot, dingy, dangerous places. They were cleaned by the mill workers as dust stuck to the linings and could be recycled back in the mill. Children weren't employed by the mill but experienced and hardy, but sadly expendable men.

Despite the efforts of these flues the surrounding land was still contaminated leaving the land sterile.

Listing Description

Both Ordnance Survey maps shown here illustrate the Allen Smelting Mill from the 1850s until the eve of its closure in the 1890s. You'll notice it was without its rail link in the 1850s as the Hexham & Allendale Railway was yet to be constructed. Product was likely shipped via horse and cart up to Haydon Bridge or Hexham. You'll see the dashed lines indicate the embankments of the flue systems, with both leading south to a chimney on Flow Moss. The flue started across the road and was taken overhead by a pipe across the road which then leads underground, with a second flue leading up to Thornley.

The 1890s map depicts the works with the branch extending from Catton Road Station, the terminus of the Allendale Railway. Wagons were shunted from an end siding into the complex, probably only fitting around 10 or so at a time.

The 1921 Ordnance Survey illustrates the mill some 20 years after closure. The railway line was severed and the shunt sidings reclaimed as a plantation. Many of the structures are intact as they are today, though many have slowly been demolished over time. The flue system is exactly as it is today.

Site of the Allendale Smelting Mill in November 2024

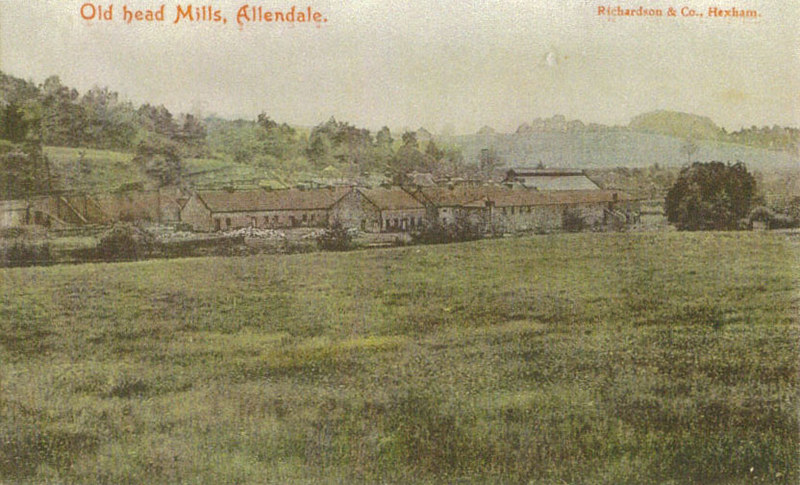

The Allen Mill in the 1890s. Source: Allen Valleys Local History Group

The flue system leading through Thornley Gate in November 2024