Winlaton, Gateshead

Crowley Iron Works, Winlaton

Last Updated:

3 Oct 2022

Winlaton, Gateshead

This is a

Metal Smelting Site

54.938982, -1.711517

Founded in

Current status is

Demolished, some ruins remain

Designer (if known):

Scheduled Ancient Monument

'The monument includes the extensive structural, earthwork and stratigraphic remains of the Winlaton Mill ironworks and its associated water supply and housing. It is situated alongside the River Derwent, which provided an abundant power supply for the range of works at the site. The sites of the earlier corn and fulling mills are also included.

Development at the ironworks commenced in 1691 when Ambrose Crowley II, the leading supplier of ironwork to the Royal Navy, took over a pre-existing corn and fulling mill. The mill works were rapidly expanded into a major integrated ironworks, including a finery/chafery forge, plating forge, slitting mill, cementation steel furnace, blade-grinding mills, anvil shop, hardening shop and nailmakers' and filemakers' workshops, together with warehouses, offices and housing. The main water-powered mills and forges were located at the north east end of the complex, with the nailmakers' workshops, warehouses and offices around two squares to the west, and the housing along the base of the hillside to the west and south of the squares.

The south west part of the site was occupied by successive leats to the millponds, fed by a large multi-phase dam and weir on the River Derwent. The river weir allowed water to be drawn off the river towards the dam complex, where it could be routed according to needs. The dam complex is known to have had at least three phases, with the latest of these incorporating an early and unusual `horizontal arch' design with a curved weir and spillway, the latter angled against the current and supplying water to the southern millpond. A stone-lined leat 3.6m wide carried water from the dam complex to the northern pool (Great Pool) that served the ironworks. This leat had at least two phases of construction and examination suggests that the silting deposits surviving at the base of the leat will hold important archaeological and environmental evidence. The larger millpond occupied much of the central part of the site, and the smaller, square millpond to the south (located just south west of a modern footbridge) served a blade mill on the site of the earlier corn and fulling mills.

The ironworks saw only limited further development from the 1720s, and began to run down after the 1780s, when the Crowley family involvement ended. It finally closed in 1863. In the mid-20th century, much of the site was progressively buried by waste from a nearby cokeworks. This was removed under archaeological supervision in 1991-2, and the well-preserved remains were reburied and the area landscaped.

The main visible features of the ironworks are therefore the remains of the dam at the south west end, and ruins and earthworks of the workers' housing along the west side. The remainder of the works site is landscaped as a public park, but the below-ground structures and deposits of the ironworks survive beneath this.

Winlaton Mill is exceptional for a number of reasons. The Crowleys were a leading family of ironmasters from the Midlands, who acquired the Winlaton site because of its potential for integrated works on a massive scale. They brought with them much of the cumulative knowledge of the Midlands ironmasters, but also supplemented this with their own innovative ideas on iron manufacture. The works is also an important early example of the factory system of production, with the site integrating iron making, manufacturing, offices, storage and housing. The area of the monument includes the entire complex, where archaeological work has confirmed the presence of extensive stratigraphic and structural remains that can provide a wealth of further detail about the site. The site also has important documentary evidence surviving, particularly a map of 1718, which records the layout and function of each of the structures at the site. The works is also famous for the set of laws that Crowley introduced, to cover the workers' daily lives and to ensure the smooth running of production. The social welfare elements of this system were in place at Winlaton some two centuries before such things were available nationally.

A number of features are excluded from the scheduling. These are: modern fencing, electricity and telegraph poles, signboards, the abutment of the `Butterfly Bridge' across the river, the abutment of the stone bridge at the south east corner of the monument, the metalled surfaces of all tracks and paths, the boulders along the north side of the pond at the southern edge of the monument and a brick and breeze-block building to the west of the trackway in the north west corner of the monument; however, the ground beneath all these features is included.'

- Historic England

Some excellent work has been undertaken in the past couple of decades on the Crowley's role in Slavery, including the manufacture of iron chains, shackles and branding irons at this very works. If you want to read more about this research, look at this excellent piece by John Charlton on the Heddon History website: http://heddonhistory.weebly.com/blog/the-slavery-business-in-north-east-england-by-john-charlton

Listing Description (if available)

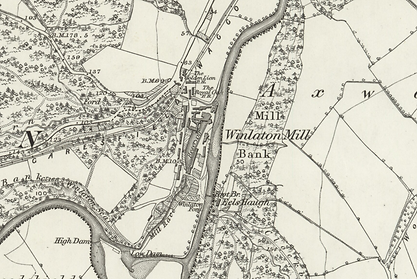

The Ordnance Survey editions above illustrate the Crowley Works after their closure in the mid century. The ruins survived into the 20th century, though ruins remain extant. Though not labelled the complex can be seen along the river, along with the Mill race.

Ordnance Survey of 1921 illustrating the complex before its full dismantlement around a decade later.

Photograph of the ruinous iron works some time after its closure. It seems nature has taken ownership of the buildings that made up the site, though various bits of machinery and a chimney can be seen. This particular building is Winlaton Mill, part of the site.

Retrieved from the Mills Archive

Photograph of the gateway and entrance to the Iron Works. The gateway can faintly be seen in between the buildings. This photograph was clearly taken well after its closure, likely turn of the century.